Sydney’s Olympic legacy

25 years on, the Sydney 2000 Games continue to shape Sydney’s landscape and identity. GML Senior Associate Dr Alison Starr reflects on the Games’ enduring cultural, ecological and community legacy.

On a cool night in September 2000, in front of 110,000 spectators, athlete Cathy Freeman lit the Olympic cauldron at Stadium Australia, officially commencing the Sydney 2000 Olympic and Paralympic Games. What followed was two weeks of near-perfect weather, showcasing the beauty and breadth of Sydney, its land and waterways and introducing, perhaps for the first time to many, the many facets of Australian sport, culture and landscape. Although Australia had hosted major international sporting events throughout the twentieth century—including the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, one of the first held after World War II—it is the Sydney 2000 Games that have become embedded in the national identity.

With extensive experience in the pre-Games era advising on industrial heritage, and more recently in providing advice to Sydney Olympic Park Authority (SOPA) to inform the Sydney Olympic Park Master Plan 2050, the Sydney 2000 Games has long been part of GML’s corporate DNA. GML’s heritage advice on the Master Plan 2050 covered identified heritage places that related to the former State Abattoir and Brickworks, and the Newington Armament Depot. Those two weeks in September were also explored in terms of the area’s Olympic legacy, including the overall design of Sydney Olympic Park, its purpose-built facilities, landscape, infrastructure, urban design and public artworks.

The Sydney 2000 Olympic and Paralympic Games were held from 15 September to 1 October, featuring more than 300 events across 30 venues. Around half of these venues were purpose-built, designed by leading architectural practices. Alongside sport, Australia’s Indigenous culture was showcased through ceremonies, performances, and a cultural festival. Planning began soon after Sydney was announced as host in 1993, with the Olympic precinct at Homebush—once a major industrial area—taking shape through the 1990s. The relocation of the Royal Agricultural Society Showground from Moore Park was pivotal, with the 1998 Sydney Royal Easter Show and major sporting events such as the rugby Bledisloe Cup providing vital tests of the new facilities ahead of the Games.

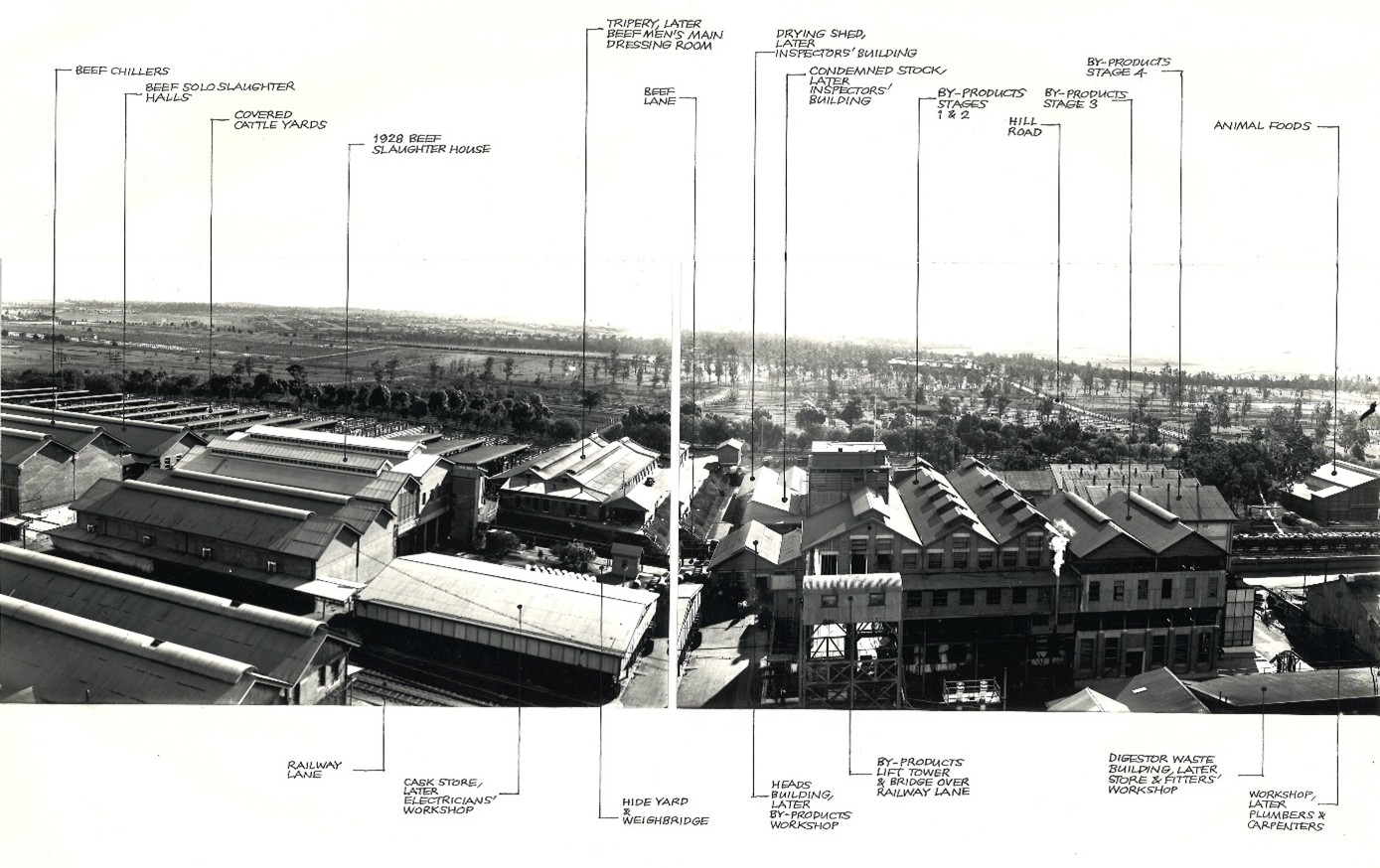

It wasn’t only sporting venues required to stage the Games but also a large-scale ecological remediation program, to restore liveability to the former industrial areas. In 1990, Godden Mackay Logan (GML’s precursor) undertook analysis and photographic recording of the State Abattoir and Brickworks (both officially closed in 1988), and Newington Armament Depot. The new State Abattoir had opened at Homebush in 1915, having relocated further west from its earlier location at Glebe. Though the stockyards have long since disappeared, the State Abattoir administration buildings remain at the heart of Sydney Olympic Park. Large fig trees, a key element in the urban design vision for Sydney Olympic Park, were relocated as part of landscape works as the area changed, having been the source of shade for livestock in stockyards surrounding the State Abattoir buildings.

Part of the former Newington Armament Depot was redeveloped as the Athlete’s Village, later becoming the residential suburb of Newington. Despite media predictions that Sydney Olympic Park would become a ‘white elephant’ after the Games, the precinct has continued to evolve—from purpose-built sporting venues into a thriving entertainment hub, workplace and emerging residential area, framed by motorways, green spaces and rehabilitated waterways. Branded the ‘Green Games’, Sydney 2000 set a bold benchmark in ecological restoration and sustainable reuse, transforming a former industrial site into a lasting urban legacy.

What remains of Sydney’s pre-Games heritage, and what might a post-Games legacy look like? Once a heavily industrialised suburb, Homebush was transformed through the ‘Green Games’ initiatives that underpinned Sydney’s Olympic bid, embedding remediation, reuse and sustainability as core design principles. Sydney met its ambitious ecological restoration targets in time for the Games, and SOPA has continued to uphold these commitments. The results are still evident today in projects such as the Brickpit Ring Walk (2005, Durbach Block Architects), which reimagines the former brick quarry as habitat for the green and golden bell frog and diverse birdlife, and in the successful restoration of Newington Nature Reserve.

In addition to the heritage items that speak to Homebush’s industrial past and the role the area played in Sydney’s economic development, the Sydney 2000 Games is presented by just two NSW State Heritage Register listings: the Sydney Olympic Cauldron (#01839), relocated in the post-Games era to Overflow Park, and the Hall of Champions moveable heritage collection (#2391). The wider precinct functions as a collection of purpose-specific buildings, interspersed with urban design responses that sought to balance the scale of Olympic crowds with the post-Games use of an area with no fixed purpose. The Master Plan 2050 sets out an ambitious agenda to achieve a vibrant, populated suburb that goes beyond the current identity of Sydney Olympic Park as a destination for large entertainment and sporting events.

Yet the Games themselves embedded both the place and its spectacle of the Sydney 2000 Games in the hearts and minds of Australians. On 15 September 2000, Sydney Olympic Park became the stage for a celebration of Australian culture: from Indigenous song, dance and ceremony to thousands of horseback riders invoking Banjo Patterson’s The Man from Snowy River, and stories of sun, sea and song woven through the Opening Ceremony. Even before the cauldron was lit, thousands had followed or cheered the Olympic Torch Relay as it wound its way across the nation, taking in World Heritage sites from Uluru-Kata Tjuta and Kakadu to the Great Barrier Reef, before arriving in Sydney. With the support of a vast volunteer workforce, the Sydney 2000 Games were declared an undeniable success.

The Sydney 2000 Games forged deep personal, community and national connections, intertwining place with the collective experience of participation and celebration. Worldwide audiences watched Cathy Freeman light the Olympic cauldron, before she became a gold medallist and role model for the nation and Aboriginal communities just days later. Olympic Boulevard thronged with spectators beneath the striking ‘Towers of Power’, which generated solar energy, served as landmarks, and embedded heritage interpretation by representing every modern Olympiad. The Games is also linked into the modern Olympic movement with Discobolus Park, funded by the Greek Australian community, designed to celebrate the centenary of the modern Olympic movement and connect Atlanta (1996), Sydney and Athens (2004). GML has recently provided heritage advice to SOPA on State Heritage Register nomination of Discobolus Park. Celebrating the 25th anniversary of the Sydney 2000 Games offers opportunity to reflect on the vast change that Sydney underwent for those two weeks in September, and the ripple effects of that change on our city, our community, and how we presented ourselves to the world.

Further reading

GML prepared a Heritage study, Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Study, and Heritage Interpretation Plan as part of the Sydney Olympic Park Master Plan 2050.